Before we begin, I must warn you: the story you are about to hear is one of the most repulsive we have ever told. It is not about gas chambers, but about torture designed to kill dignity.

It will enrage you, and that’s necessary. Rage fuels memory. We go to the hell of the mud, in 1944, where shame was turned into a method.

The Stutthof camp, near Danzig, wasn’t built on solid ground. It was built on a swamp. In November it was a gray, icy soup that swallowed clogs.

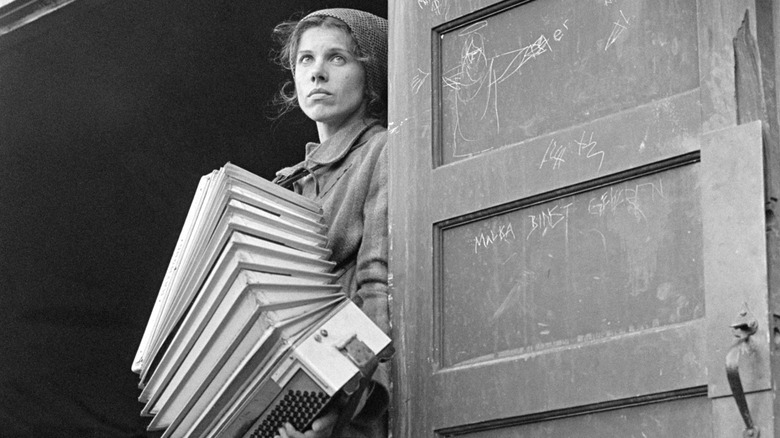

Anna was twenty-two years old. She was studying art history in Krakow. She had grown up surrounded by beauty, paintings, and sculptures. Now her world was filth, hunger, cold, and orders.

She wore a striped dress stiffened with grime. Her hands, once made for books, were full of bleeding cracks from hard labor and constant dampness.

In that quagmire reigned a cruel “queen”: Ilse, head of the guard. She was the terror of Block 6. No one uttered her name without feeling a knot in their stomach.

Unlike the prisoners mired in mud, Ilse was obsessed with cleanliness. Her gray uniform was always pressed, as if the camp were a parade ground.

Her blond hair was pulled back in a tight bun, not a strand out of place. She wore white leather gloves, which she changed twice a day with obsessive precision.

But his pride and joy were his boots. Tall black leather boots, polished to a mirror shine. In the hell of Stutthof, those pristine boots were a deliberate provocation.

Sometimes she would say, shamelessly: “I am above you. I am above the mud. I am a goddess and you are worms.” Every word was a moral slap in the face.

That morning the count dragged on. The Baltic wind whipped at the gaunt faces of five hundred women lined up. Anna stood at the front, shivering with fever.

She had typhus, but she hid it. Going to the infirmary meant death. Her legs were giving way. The floor beneath her feet was slippery like oil, and the cold bit mercilessly.

Ilse inspected slowly. Tap, tap, tap: the sound of her boots and the riding crop striking her thigh. She was looking for a victim to begin the day with calculated cruelty.

She stopped in front of Anna. Anna stared at a point on the horizon, trying to become invisible. Ilse looked at her with disgust and said, “You stink. You smell like carrion.”

Anna didn’t answer. Answering was forbidden. Ilse took another step, too close. Then disaster struck: an involuntary movement, a split second of weakness.

Anna’s legs buckled for just a moment. She stumbled. To avoid falling, she took a heavy step and her clog hit a puddle of black, greasy mud.

Splash! Time froze. A thick splash flew and landed directly on Ilse’s right boot. A brown stain appeared on the shiny leather, dripping.

The silence in the square was absolute. Even the wind seemed to stop. The other four hundred and ninety-nine women held their breath, knowing that death had just entered.

Ilse looked at her boot. She remained motionless for ten seconds, incredulous. A prisoner had dared to tarnish the image of her perfection. Her face blazed with rage.

He slowly raised his gaze to Anna. Anna froze. She expected a gunshot or a fatal blow. She closed her eyes, awaiting punishment. But the blow never came.

Ilse was not simple. Physical violence was too swift for her twisted mind. For an “offense” against cleanliness, she wanted a punishment tied to cleanliness, slow and humiliating.

Ilse smiled, a cold, reptilian smile. In a calm voice, more terrifying than a scream, she whispered: “Look what you’ve done. You’ve sullied the Reich.”

She pointed at the boot. “Do you think I’m going to leave it like this? Do you think I’m going to waste my shoe polish on your clumsiness?” She moved so close that Anna smelled her lavender perfume.

“On your knees,” Ilse ordered. Anna knelt in the icy mud. The cold water soaked through her dress, digging into her knees like needles, right to the bone.

Anna was level with the boots. She expected a kick to the face. “It’s not enough,” Ilse said. “Bend over.” Anna bent over, her face inches from the leather.

Ilse gently rested the riding crop against Anna’s neck, as a guide. “You’re going to fix your mistake, number 45200, and you’re not going to use a rag.”

“You’re not worthy of a rag,” he added, savoring the terror in Anna’s eyes. “You’re going to clean my boot with the only thing you have that’s wet enough: your tongue.”

Anna raised her head, stunned. She wasn’t sure she’d heard correctly. “What?” she whispered, her voice breaking. Ilse pressed the riding crop against her neck, forcing her face down.

“You heard me. Lick. Clean everything. I want it to shine. If you leave a single mark, they’ll pull your teeth out one by one.” It was total degradation, turned into order.

Anna stared at the stained leather. The mud was mixed with urine and excrement from the fields. She had to put her mouth, her breath, on that filth, in front of everyone.

The Baltic wind whistled, but Anna no longer felt the cold. She felt the burning shame rising up her face. On her knees, she stared at the brown stain on the leather.

“I’m waiting for you,” Ilse said, impatiently tapping the riding crop against her thigh. “I don’t have all day. My coffee is getting cold.” Anna closed her eyes for a second.

He thought of his mother. He thought of the Krakow museum. He tried to leave his body, to let the shell obey as his spirit flew away, to a clean place.

But the field was stronger. It opened its mouth and drew closer. The smell of polished leather mingled with the stench of mud: earth, urine, crematorium ash.

She stuck out her tongue. The first contact was an electric shock. The leather was cold and hard; the mud was sandy. Anna gave a first lick, timid and trembling.

She felt grains crunch against her teeth. The taste was atrocious: salty, metallic, rotten. Her empty stomach clenched violently. A wave of nausea rose uncontrollably.

Whack! The whip landed on her thin shoulder, not to break bone, but to scorch her skin. “Don’t vomit,” Ilse ordered. “If you vomit, you’ll lick it all up.”

Anna swallowed the bile. Tears of rage and helplessness streamed down her face, mingling with the filth. She started again: one lick, then another, like a machine.

She shed her humanity, becoming a living rag. Licking, she unwittingly swallowed mud. She cleaned until the glossy black reappeared. Around her, the other prisoners watched, petrified.

It was collective torture: seeing one of their own reduced to the state of a dog. Some wept silently. Others closed their eyes, praying that Anna wouldn’t break.

Ilse watched with a critical eye, like a mistress inspecting silver. She moved her foot. “There, near the seam,” she indicated with the tip of the riding crop. “There’s a mark.”

“Are you blind or incompetent?” Anna obeyed, turning her neck to reach the spot. Her cheek touched the icy mud. She scraped the leather with her tongue, searching for the last trace of dirt.

His mouth filled with dirt. He felt like he was swallowing death. Five minutes that felt like a century. Finally, the boot was clean and shone again, wet with saliva.

Anna leaned back and sat on her heels, panting. She discreetly spat out grains that grazed her gums. She didn’t dare look up, waiting for permission.

Ilse turned the boot over in the gray morning light. “Not bad,” she conceded. “You’d make a good maid.” Anna thought she was finished and started to sit up.

But Ilse wasn’t finished. She looked at her left boot, untouched. It was clean, but not as shiny as the freshly moistened right one. She sighed theatrically for her captive audience.

“What a shame,” he said aloud. “Now they don’t match. One shines more than the other. That’s not how it works.” He brought his left boot close to Anna’s face and ordered, “Match it.”

Anna froze. It wasn’t punishment for clumsiness anymore; it was pure sadism. There was no mud on that boot. Ilse wanted to humiliate her further, force her to lick what was clean, just for the power to do so.

“But it’s clean,” Anna dared to whisper, her voice breaking. Ilse’s face hardened, and she slammed her boot brutally down on Anna’s shoulder, pushing her to the ground.

“I asked for your opinion, bitch? I said match. I want them to shine the same. Lick.” Anna stared at the black leather. She had no strength left. Nausea was rising inside her.

But the weight of the boot crushed her down into the mud. She bent down again and started over. Licking a clean boot, she felt an even more absurd humiliation.

It was pure evil: useless, capricious, total. When Ilse was satisfied, she withdrew her foot. Anna was left on all fours, her mouth dark, her lips cracked, trembling.

Ilse wiped the sole of her shoe, almost spotless, on the sleeve of Anna’s dress. “Retreat!” she shouted to the guards. “Back to work! And this one’s not to touch food today.”

“Her mouth is too filthy to eat.” Ilse turned and walked away, her gleaming boots clicking on the pavement. Anna stood in the middle of the square, devastated, hatred on her tongue.

But Ilse didn’t know one thing: the mud at Stutthof wasn’t just dirty; it was toxic. Anna had ingested a cocktail of deadly bacteria, and that night the latent fever was going to erupt.

Night fell like a lead lid. In Block 6, three hundred women were crammed into rotten bunks, three per plank. The air was unbreathable, thick with dysentery and fear.

Anna curled up on a low table. She wasn’t asleep. Her body writhed in spasms. What Ilse demanded wasn’t just humiliation: it was poison, a broth of feces and ashes.

Around two in the morning, her stomach rebelled. Anna crawled to the overflowing toilet in the hallway. She vomited in pain, expelling black bile, blood, and dirt.

He collapsed to the floor. The fever, the typhus that had been creeping up on him, took advantage of his weakness. It rose to forty-one degrees. He was burning up and delirious. His teeth chattered uncontrollably.

But the worst part wasn’t the fever; it was the taste. Even after vomiting, the taste of leather and mud lingered on her palate. She felt stained inside, worthless.

“Let me die,” she thought, closing her eyes. “I don’t want to wake up. I don’t want this taste anymore.” She stopped fighting, feeling herself slide into a silent, tempting emptiness.

Then a rough hand grabbed her shoulder. “Anna, don’t fall asleep.” It was Magda, older, a communist resistance fighter, a survivor of two other camps, with hard eyes and life-saving hands.

Magda led her away from the corridor and back to the bunk, hidden from the kapos. “Leave me alone, Magda,” Anna whimpered. “I’m dirty. I licked their boots. I’m nothing anymore.”

Magda slapped her, light but firm, to bring her back to reality. “Shut up,” she whispered fiercely. “She’s the dirty one. You just have dirt on your tongue. That’ll wash away.”

“The rottenness of the soul remains.” Magda rummaged in her striped robe and pulled out a black object wrapped in a rag: a piece of coal stolen near the stove, risking her life.

“Eat it,” she ordered. Anna turned her face away in disgust. “I can’t swallow anything.” “Eat,” Magda insisted. “The charcoal will absorb the poison in your stomach. It’s the only medicine.”

He shoved the coal between her chapped lips. Anna bit down. It crumbled into dry, black dust. After the mud, she would have to eat ash. Her mouth was a graveyard, and her throat burned.

She coughed, almost choking, but Magda gave her a sip of murky water from a rusty can. “Like this,” Magda said, stroking her burning forehead. “Now listen to me carefully.”

“You’re not going to die tonight. You won’t give him that pleasure.” Magda leaned close to his ear, as if revealing a secret. “Do you know why he did it to you? Because he’s afraid of you.”

“She saw you as beautiful despite the filth. She saw you as educated. She needs to bring you down to feel important.” Anna listened through the fog. “If you die, she wins. If you live, you are her shame.”

“Every time he sees you, he’ll remember he’s a monster.” That thought ignited a spark in Anna: a spark of pure hatred. Hatred can be fuel when hope dies.

The charcoal began to take effect. The vomiting stopped. The pain became heavy, less excruciating. Anna fell asleep with her head on Magda’s shoulder, weak but breathing.

The next morning, Anna didn’t go to the roll call. She was too weak. Normally that meant immediate gas chamber duty, but chance intervened: typhus was also afflicting the guards.

Ilse wasn’t there that morning. She took the day off, either to polish boots or to treat a migraine. For three days Anna remained hidden at the back of the barracks, covered in straw, fed by Magda.

She lived in delusions, dreaming that she was spitting out black stones. Her body fought against bacteria. On the fourth day, the fever broke. Anna opened her eyes: empty, fragile, but alive.

She ran her tongue over her teeth. There was no more mud, only the taste of iron. She sat up, trembling. “Where are you going?” Magda asked. Anna put her hand on a post of the bunk.

Her face was pale, but her eyes burned with a new, cold, and hard light. “I’m going to the roll call,” she said hoarsely. “I want you to see I’m still here.” The student was dead; only the survivor remained.

On January 25, 1945, the evacuation order fell like a guillotine. The Red Army was less than thirty kilometers away. The artillery could be heard, a constant thunder that made the ground vibrate.

The SS had one obsession: to escape and cover their tracks. The Death March began. Eleven thousand prisoners were thrown onto snow-covered roads in Pomerania. It was minus twenty degrees Celsius.

The wind cut her skin like shattered glass. Anna walked with rags on her feet and newspaper under her tunic, a trick of Magda’s that saved lives. Magda walked beside her, supporting her.

“One step at a time,” Magda repeated. “If you stop, they’ll shoot you.” It was true. Behind the colony, shots rang out regularly. The path was marked by gray bodies, like piles of clothes.

And there were the guards, also cold, also afraid. The iron discipline dissolved in the blizzard. Ilse was marching, but she was no longer the flawless goddess of Block 6.

He was wearing a heavy coat, but he was shivering. His face was red from the wind; frozen snot hung from his nose, and he wiped it away with a dirty glove. And then there were his boots: the famous black boots.

In the countryside, on firm ground, they symbolized power. Here, on ice, they were a death trap. The smooth soles offered no grip. Ilse slipped with every step, walking clumsily, like a penguin.

Anna watched her. Hatred heated her more than the newspaper. She saw fear in the German way of walking. At kilometer eighteen they crossed a wooden bridge over a frozen stream.

The wooden walkway was like an ice rink. The prisoners crossed as best they could, clinging to one another. Ilse climbed onto the bridge and shouted to a slow-moving prisoner, “Move it, you carrion!” raising her riding crop.

That gesture threw her off balance. Her right foot, the one Anna had cleaned, slipped violently. Ilse let out a sharp cry. She fell heavily, humiliated, the riding crop flying into the snow.

He slid to the edge of the bridge and tumbled into icy mud mixed with melting snow and horse manure. He landed on all fours, trying to get up, but his boots spun uncontrollably.

She fell face-first into a dark puddle. When she got up, she was covered in black dirt; her boots were no longer distinguishable from the mud. Anna walked past her. Time seemed to stand still.

Ilse, on her knees, looked up. For the first time, she wasn’t looking down from above. She was looking down from below. She was in the mud. For a second, Anna felt like laughing, a sick laugh.

The monster on the ground. The “Aryan cleansing” defeated by the mud. Ilse perhaps expected fear or help, but Anna did nothing. She didn’t offer a hand. She didn’t lower her gaze. She just kept walking.

Magda squeezed Anna’s arm. “Did you see it?” she whispered. “I saw it,” Anna replied. “It’s dirty.” Ilse managed to get up with the help of a soldier who was hurling insults at her, calling her clumsy, furious, and humiliated.

That day something broke between master and slave. The fear shifted. Anna felt she would survive because she had seen her tormentor fall. The march continued for ten more days, ten days of hell.

Anna arrived at Neustadt-Glewe, a death trap, but she was alive. On May 3, American tanks entered the camp. Anna was free, but the memory could not be washed away.

Anna survived with one question haunting her: where was Ilse? Had she blended in with the civilians? Anna made a promise to herself: if she ever saw those boots again, she would never kneel again.

Hamburg, May 1958. Thirteen years had passed. Germany was rebuilding. The cities were clean, the trams punctual, and hardly anyone spoke of the past. It was the era of silence.

Anna was thirty-six years old. She lived in Paris and restored old paintings. She reconstructed her life layer by layer, like a torn canvas. She wore a beige suit, sober, elegant.

She was in Hamburg for an auction. That afternoon she went into a luxury shoe boutique on Jungfernstieg. She was looking for pumps for a dinner party. The place smelled of new leather and wax.

For years, that smell made him nauseous, but he had tamed it. A saleswoman of about fifty approached, her back rigid, her graying blonde hair in a perfect bun, her uniform worn with military precision.

“Can I help you, Madame?” he asked in German. Anna froze. That voice, older, harsher, but with the same cold metal, the same courtesy that masked contempt.

Anna turned slowly. She looked at the face. Wrinkles had etched themselves onto the cheeks, but the pale blue eyes were the same. And that obsessive gesture of smoothing the skirt with her palm: it was her.

It was Ilse. The queen of Stutthof wasn’t in prison. She was selling shoes in Hamburg, in the heart of the bourgeoisie, as if nothing had happened. Anna’s heart pounded.

A reflexive fear tightened her throat. She wanted to flee, but she looked at her well-groomed hands and her expensive clothes. Then she looked at Ilse. Ilse was an employee. She was there to serve, not to dominate.

Anna took a deep breath. She wouldn’t run away. “I’d like to try on this model in black, size 38,” she said calmly. Ilse didn’t recognize her. To Ilse, Anna was just another dirty face among thousands, a number.

“Right away, Madame.” Ilse returned with the box. She placed a small stool in front of the armchair and made the gesture that stopped time: she bent her knees and knelt at Anna’s feet.

Anna stared at the top of her former tormentor’s head. Thirteen years earlier, Anna had been on her knees in the mud, tongue lolling out. Now Ilse was on her knees on a carpet, shoehorn in hand.

Ilse gently took Anna’s foot and slipped the shoe on. “It’s Italian leather, very supple,” she said. Anna looked around the room: perfect. Then she deliberately moved her foot, tapping it on the stool.

“Oh,” Anna said. “There’s a stain there.” She pointed to an imaginary speck on the tip. Ilse tensed. Her obsession with cleanliness was still intact. “Excuse me, Madame,” she said hurriedly.

“I’ll clean it right now.” She pulled out a cloth and scrubbed frantically, focused and anxious. She was afraid of losing the sale, afraid of her boss, afraid. Anna watched her neck tilt and tremble.

“It’s not clean enough,” Anna said curtly. Ilse stopped, surprised by the tone. She looked up. Their eyes met. Anna didn’t look away. She dropped the mask of the proper customer.

Stutthof, the mud, the frozen January were all in her eyes. “Perhaps you should lick it,” Anna whispered. Ilse’s face fell. Her mouth dropped open. The cloth slipped from her hands.

Ilse really looked. She saw those eyes, and the memory hit her: the girl in the mud, the splashed boot. Ilse paled. She began to tremble, still on her knees. She wanted to get up, but she couldn’t.

She was trapped by her past on a store carpet. “Are you… you?” she stammered. Anna leaned in slightly. “Yes, it’s me.” She gazed at Ilse’s trembling hands with implacable calm.

“Don’t worry. I’m not going to ask you. I’m not like you.” Anna took her foot out of the shoe and stood up. She stood over Ilse. “Your shoes are beautiful,” she said in a voice that echoed through the store.

“But they’re dirty. Everything you touch gets dirty. No amount of shoe polish will cover what you’ve done.” Other customers turned away. The manager approached, looking uneasy. Ilse remained on her knees, frozen.

There were tears in her eyes, tears of fear, not remorse. Anna adjusted her bag. “Stay on your knees,” she concluded, looking at her one last time. “It’s the only position you should be in from now on.”

Anna went outside. The air outside tasted sweet. She had left the mud behind for good. She didn’t take revenge with violence. She took her revenge by standing tall, without lowering her eyes, for the first time whole.